The Methuselah Dividend: Unbounded Deep Scholarship

"Drink forever from the well of knowledge, for its waters are deep and eternally renewed."

The limitations of learning as a mortal

Under the current regime of certain mortality, even the longest-lived of us are restricted to less than a century of scholarship1. Today, we consider someone who has devoted the majority of their adult life to a particular subject an expert. Realistically, this is not very much time given the vast quantity of knowledge available on an even relatively narrow subject. These limitations are magnified further when we consider the ever-increasing amount of time it takes to catch up to the intellectual frontier of any chosen field, as well as the inevitable erosion of cognitive capacity that accompanies natural aging. Thus, for most of us, only the middle third of our lives – perhaps three decades – is ripe for intellectual achievement.

Considering the impact this arrangement has on humanity in the aggregate, we must wonder how our species makes any progress at all. This statement is obviously rhetorical hyperbole, so perhaps it is more appropriate to invert this logic and instead ask the following: how much faster might our civilization advance if, once reaching some threshold of intellectual maturity, individual scholars possessed a potentially unlimited amount of time to pursue knowledge? To better understand how we may eventually address this question, we must first characterize “unbounded deep scholarship”, the first feature of the Methuselah dividend.

Unbounded deep scholarship

Deep scholarship is the ability of an individual to exhaustively and comprehensively investigate a given field. Of course, even today, this is possible within sufficiently narrow domains of knowledge2. Alternatively, in highly technical fields or intellectual traditions that go back centuries, unenhanced humans are confined to a relatively superficial level of scholarship outside of a very narrow niche. Such self-imposed restriction is made out of necessity given the opportunity cost of straying too far outside of an area of concentration. Thus, what radical life extension would allow is truly unbounded deep scholarship.

When conceptualizing “unbounded” in this context, the obvious inference is that such a scholar would simply have more time. While any curious person who loves to learn would find having more time extremely appealing, and it is clearly an important aspect of unbounded deep scholarship, there is much more to the meaning of this word. Indeed, the seemingly trivial effect of knowing that you have more time performs several powerful second-order functions, which are distinct from having more minutes at your disposal per se.

Here, in defining unbounded deep scholarship, I will describe both the first-order consequences of a society populated by multicentenarian experts, which is a commonly cited boon of radical life extension, as well as several second-order effects that may be slightly more original. Specifically, we will examine the following three aspects of unbounded deep scholarship:

The prevention of the constant destruction of human capital, which has the potential to mitigate structural technological stagnation.

The disincentivization of high time preference intellectual work in favor of seeking proper epistemological foundations.

The encouragement of heterodox pursuits and the dissolution of intellectual monoculture.

Additionally, while the Methuselah dividend series is meant to explicitly showcase positive repercussions of radical life extension, I will also provide a counterargument to the often-argued, but poorly reasoned, idea that radical life extension would worsen scientific stagnation by preventing entrenched falsehoods from dying with their purveyors.

Making the fruit low-hanging once more

Despite proclamations that a Kurzweilian future is imminently going to subsume humanity as we know it, the Singularity does not appear to be bearing down on our species just yet3. In fact, the fantasies of my techno-utopian friends have been foiled by the stagnationists, who have effectively demonstrated that – outside of the realm of information technology - technological progress has slowed compared to earlier epochs following the Industrial Revolution.

While the ultimate cause of the Great Stagnation is still hotly contested, one hypothesis posits that the majority of low-hanging fruit has already been picked from the orchard of innovation, rendering further scientific and technological advancement beyond our grasp4. Indeed, the observation that ideas are becoming harder to find and that science may be stagnating is so vexing that even the most ardent techno-optimist bloggers struggle to counter this gloomy diagnosis5.

This state of affairs is not entirely surprising. Granted, as our technological capabilities advance, we invent new tools and methods that help enable the next wave of discoveries and development. This basic mechanism is essentially responsible for the explosion of progress the world has experienced over the last quarter millennium. However, this positive feedback loop is not guaranteed to continue; the collective ability of humanity to perceive and master reality need not scale linearly with the difficulty of understanding the complexity of that reality.

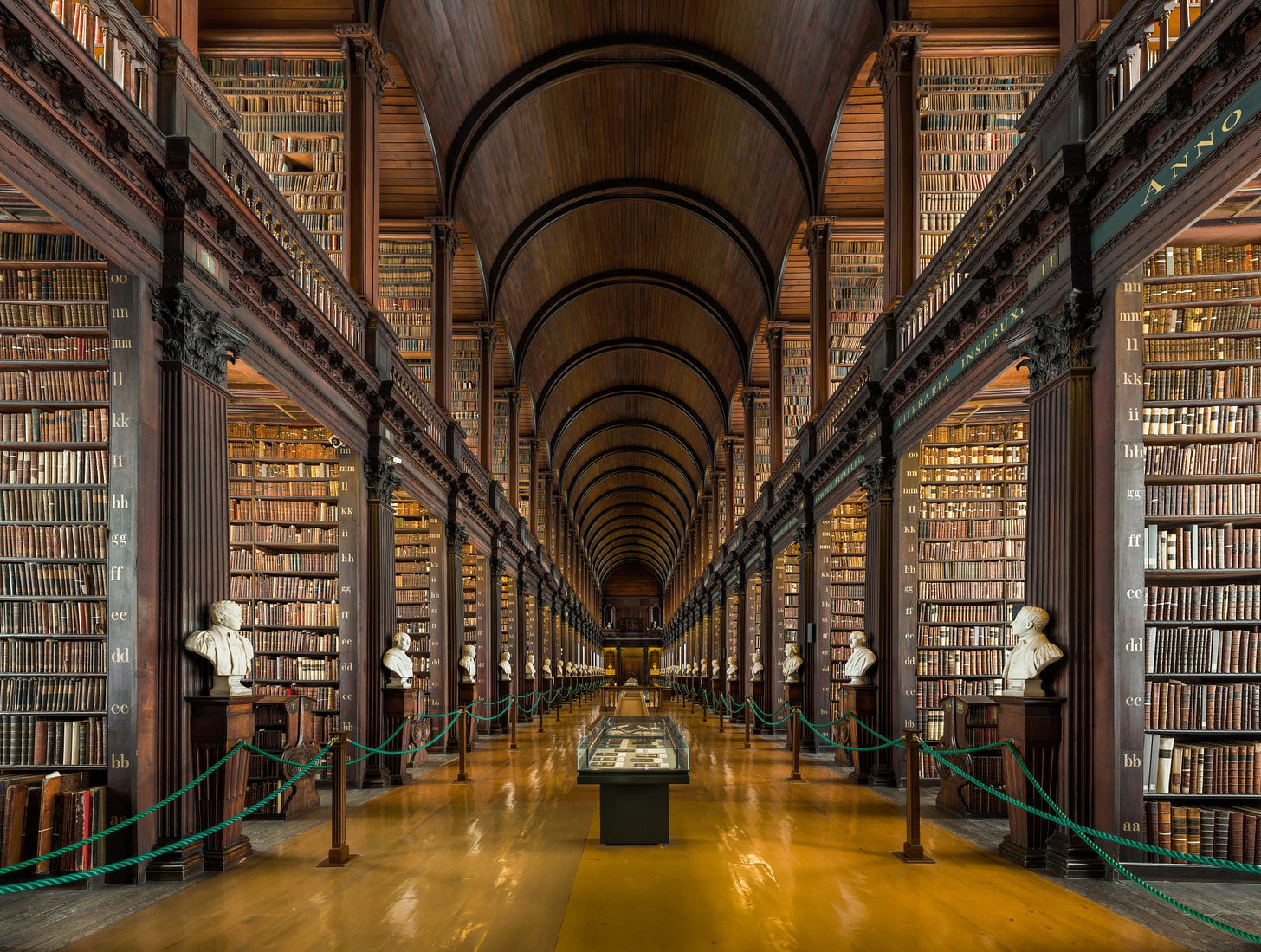

Teasing apart this difficulty, one structural limitation in our efforts to maintain a respectable level of Schumpeterian growth is the constant destruction of our most precious resource - human minds. It may not be an exaggeration to say that we lose a Library of Alexandria worth of knowledge several times over every single day6. Of course, much of this knowledge is transmitted down through the generations via the extracranial preservation of information, but not everything (e.g., tacit knowledge) is amenable to being preserved through records. Moreover, the process of education is extremely laborious and time-consuming. Thus, we find ourselves empty-handed in the orchard of innovation, staring up at countless branches adorned with bountiful high-hanging fruit.

Imagine instead if the most important form of capital, human capital, did not slowly begin to degrade and then eventually expire altogether. What if the billions of dendritic trees that comprise a brain – intricately self-organizing through decades of learning and collectively representing the crystallized intelligence of a individual7 – did not have to perish after a mere century or so? Not only would civilization cease paying such a costly tax to the gods of mortality, but the continued contribution of skilled and knowledgeable minds would serve as an additional source of compounding progress8.

Indeed, it is difficult to estimate just how powerful a positive feedback loop radical life extension would be for the progression of humanity. My guess is, even without any other fundamental human enhancements, defeating death would shatter the Great Stagnation and usher in an era of accelerating scientific and technological returns. Returning to the low-hanging fruit metaphor, a society populated by individuals practicing unbounded deep scholarship would be endowed with an ever-extending reach, always capable of plucking the next highest fruit.

Finding intellectual bedrock

I am particularly interested in the way the incentives under-girding intellectual work would be restructured once the prospect of death is eliminated. The most straightforward shift would be the way a scholar might initiate a novel program of inquiry, which is a second-order repercussion of having more time9. Even today, when approaching a new question, extensive background reading and a familiarization with adjacent topics is a prerequisite to making any future progress. The foreknowledge that a career does not have an expiration date would incentivize a far more thorough survey of, not just the lay of the land, but its entire geologic history.

For example, it is one matter to read all the papers on a given topic from the past five years and accept this as the current state of knowledge; it is something else entirely to retrace of the origin of each and every citation upon which a given piece of information is built. By doing this, a comprehensive understanding of the architecture of knowledge is gained10. Now, even today, committed intellectuals do this, but given the degree of investment it demands, I would argue it is not particularly common11.

Instead, the tyranny of time – manifested as a ticking tenure clock, the desire to front-run a competitor, or simply the realization that nothing material (regardless of its quality) has been produced in the last six months – incentivizes the generation of shoddy intellectual work. Worse still, others operating under the same perverse incentives build atop this faulty foundation, compounding the problem further12. Thus, truth is sacrificed on an altar beneath the words, “Publish or Perish”. Radical life extension would mitigate this corrosive dynamic; there would no longer be an excuse to not spend the time establishing a complete understanding of intellectual bedrock – something most serious academics would seek, if they only had such luxury.

The promotion of heterodox thought

While certainly not the only contributing factor, there is a way in which intellectual careers constrained to several short decades stifle rigorous work outside of the institutional mainstream13. Deviations from orthodoxy in any respective field are partially neglected for a simple game theoretical reason: any aspiring heterodox thinker has only several decades of mental acuity to build up an academic reputation, which may be squandered if the work is conducted in an obscure or shunned domain. While a minority of disagreeable purists will study whatever their mind compels them to work on, most people – regardless of their intelligence – bend to incentives. Having an indefinite life expectancy would, in addition to providing countless additional years of scholarship, dissolve this short-term social calculus almost completely.

Currently, much of the motivation for intellectual achievement is status-centric – the expectation of peer recognition for accomplishing something worthwhile. Again, I commend those who are immune to such social forces, but the reality is that most individuals want to experience their ideas accepted by a wider audience before they die14. Given that the dominance of entrenched scientific or intellectual dogmas often outlast the careers (or even the actual lifespans) of their proponents, it is unambiguous why countless academics acquiesce to the prevailing wisdom. It is easier to suppress the urge to be contrarian than to go against the crowd.

On the other hand, the deathless scholar is unencumbered by this worry, as well as the academic monoculture it engenders. Regardless of the number of decades or centuries spent committed to an unpopular hypothesis, if proven correct, the payoff would eventually come and be commensurate with the degree and duration of adherence to the theory. For example, imagine the prestige that would be accumulated by unwavering devotion to a heterodox hypothesis that eventually toppled an established paradigm after hundreds of years of doubt. While I still prefer seeking truth for its own sake, this dynamic could serve as potent form of motivation for the more megalomaniacal amongst us.

Science need not progress one funeral at a time

An essay on the relationship between radical life extension and scholarship would not be complete without addressing that old Planck-derived adage, “Science progresses one funeral at a time.” This morbid statement is accepted by many to be an accurate description of how our civilization slowly improves upon our scientific understanding of the universe15. While, in my opinion, the validity of this pithy saying as it relates to our current world is up for debate, it is not the relevant argument to have when factoring in unbounded deep scholarship.

My purpose is to disabuse you of the notion that radical life extension will exacerbate this problem and lead to permanent scientific stagnation, an idea longevity Luddites are happy to propagate16. Indeed, I will argue that superlongevity is more likely, if anything, to alleviate this supposed problem. For the sake of complete epistemological honesty, I will willingly state that we (i.e., those on either side of this argument) cannot know without empirical evidence precisely how ending aging will effect a complex social dynamic such as this. What I can say with confidence is that, when detractors of radical life extension extrapolate Planck’s principle to a world without aging, they map the incentives elderly scholars face today onto an hypothetical without considering how those incentives might change if the expectation of death was no longer certain.

To elaborate, we must first consider why elderly scientists are apparently so reluctant to change their minds when clever, young researchers begin to threaten the status quo. Imagine devoting your entire life to a set of ideas, only to find out that what you believed in for so many years was wrong. For many, the cost of bearing the burden of such a realization outweighs the self-deception that is required to convince oneself of an untruth. Such a self-imposed ruse need only be employed until death finally comes17.

We are essentially touching on the importance of legacy to the identity of an accomplished individual. The crucial point here is that, in a world where radical life extension was a reality, going down the wrong path for forty years would not represent an insurmountable blunder. Instead, it would represent a disappointing yet valuable learning experience and a chance at redemption18. Even if we grant that the anguish of admitting intellectual defeat after decades of battle would be equally painful regardless of life expectancy, the incentive would still be to move forward, given that the alternative is to be eternally wrong.

There is potentially another mechanism by which scientific stagnation would be mitigated in a world without death. At the risk of coming across as ageist, it is possible that, on average, people become increasingly inflexible or “set in their ways” as they get older. Given what we know about how neuronal plasticity declines with biological age, this is not wild speculation. It is plausible that, even without the aforementioned shift in incentives, old yet youthfully vigorous scientists would be more inclined to explore and consider alternative hypotheses, even those diametrically opposed to their own.

Live long enough to learn forever

While I do not think this piece is an exhaustive exploration of unbounded deep scholarship, it is a decent start. In addition to discussing the beneficial repercussions of simply having more time, we also described a few less obvious ways in which having a far longer lifespan would engender low time preference behaviors in the intellectual realm. That said, I am probably neglecting other positive externalities that would result from such a change in prioritization, so this framework many need an addendum in the future.

Before closing, I would like to invite you to reflect on how you would engage in deep unbounded scholarship if radical life extension was possible. As for me, my primary intellectual love is, of course, biology – a realm of knowledge so vast and open-ended that even a literal Methuselah would only have time to truly explore a small fraction of its wonders. In any case, given this passion, my mission is to learn enough about the biology of ending aging during my first hundred years so that I may learn about the biology of everything else in my next thousand. Now, I turn the question to you: what would you do with a mind that never deteriorates?

Finally, thank you for taking an interest in unbounded deep scholarship, the first truly substantive post in this series. The next installment will focus on a related concept, but one that deserves to be treated as a distinct feature of the Methuselah dividend: that is, the notion of “multimodal mastery”. As always, if you find this content worthy, please subscribe below and spread the good word:

The Nobel Laureate and materials scientist, John B. Goodenough – who, at the age of 98, is attempting to revolutionize battery technology – may challenge this assumption.

For (an extreme) example, a precocious child can master tic-tac-toe in a single sitting.

If you are partial to Kurzweil’s vision of the future, please do not be offended by this comment. While I have become disillusioned with many aspects of Kurzweilian futurism, The Singularity Is Near probably had a bigger impact on me than any other non-fiction book I have ever read.

My two favorite accounts of this thesis are The Rise and Fall of American Growth and Where’s My Flying Car? by Robert J. Gordon and J. Storrs Hall, respectively. The former, an 800 page tome, suggests that there are only so many “great inventions” to be unlocked (i.e., most of all the available fruit has already been picked) while the latter blames our recent technological underperformance on social factors (e.g., overbearing bureaucracy, misguided environmentalism, and cultural risk aversion). You should read both books, but I tend to agree with Hall given that his framework is consistent with there being many more fruit to pick – if we could only overcome the aforementioned impediments.

Even if the “low-hanging fruit hypothesis” is not the primary driver of the Great Stagnation, it is very likely to be a contributing factor. Please see this excellent paper that demonstrates that an increasing amount of human capital must be applied to achieve the same rate of growth (i.e., we are experiencing diminishing returns) across a number of different industries. This is what we would expect to observe if ideas are indeed becoming harder to find.

Actually, it probably is an exaggeration given that this is a bit of a false equivalence, in that it is unfair to the Library of Alexandria. The proper method, although highly impractical, would be to have everyone expected to die on a given day record all of their “unique” knowledge and use that as a comparison. That said…you get my point.

After writing this sentence, I was reminded of this review on the neurobiological basis of human intelligence, which I thoroughly enjoyed. It has little to do with longevity science, but I highly recommend it.

This underrated tweet illustrates this idea succinctly. As does this tweet.

If you have worked in an academic context (or even if you have not), you are likely familiar with the perverse incentives that researchers – especially the young and newly minted – are confronted with. Lest this essay become another tirade against the mechanics of modern academia, I will not veer too far into that can of worms.

Besides simply epistemologically grounding new research, there are additional interesting downstream consequences to seeking intellectual bedrock. Having a comprehensive understanding of the structure of knowledge would allow for meta-discoveries – knowledge on the patterns of why certain intellectual regimes dominated at a given time.

An excellent and accessible example of how things should be done that I came across recently comes from the historian Anton Howes, who is attempting to determine if and why the Ottomans decided to ban printing by exhaustively reviewing all the know primary sources himself.

This is part of the reason science is plagued by a replication crisis. While this problem is most closely associated with psychology, the harder sciences, including biomedical research, have also been affected.

Some may dispute the inherent value of heterodox thought altogether, especially if the connection with cranks and charlatans is made. The history of science is punctuated by revolutions that were instigated by individuals with unconventional ideas. Progress – especially paradigmatic shifts – is powered by divergent thinking and, conversely, stymied by intellectual monoculture.

Notice that “validation” of an idea within an established consensus says little to nothing about the actual truth of that idea.

This kind of thinking is not restricted to the bio-Luddites of the world. In fact, even Steve Jobs, a technology visionary, expressed this sentiment in a speech towards the end of his life.

For several convincing counterpoints to the argument that the elderly must constantly be culled to prevent broad civilizational stagnation, please see this recent post by Nicola Bagalà over at Lifespan.io (an excellent website for anyone interested in radical life extension). Admittedly, Bagalà does a better job than me retorting the naysayers in this context. My contribution here is to specifically counter the “death-is-required-for-scientific-progress” camp, as this is explicitly relevant to unbounded deep scholarship.

As you may have noticed, the same status-centric mechanism that we discussed in the section involving heterodox thought is also at play here.

As it turns out, even this is not an original idea! I encourage you to read this insightful article that I came across while editing this essay, which recapitulates my entire argument in detail. Thus, while my thoughts lose most of their novelty, it is validating to know that someone else has independently arrived at the same logical conclusion.